Breaking Down the Autism Diagnosis

Autism is a complex, lifelong neurodevelopmental disability that affects essential human behaviors such as social interaction, the ability to communicate ideas and feelings, imagination, self-regulation, and the ability to establish and maintain relationships with others. Although precise neurobiological mechanisms have not yet been fully established, it is clear that this disability reflects the operation of factors in the developing brain.

In the United States, clinicians use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) to diagnose autism. The DSM-5 is important because it provides the diagnostic labels that governments, insurance companies, and other institutions use to determine the services needed by each individual. To receive a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), an individual must show traits in two major areas. The DSM describes these as:

- Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

- Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

2. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

- Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

- Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

- Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g. apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

The Diagnosis in Simpler Language

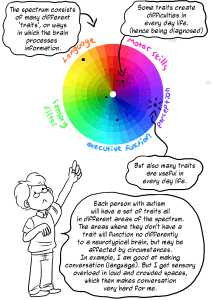

The DSM-5-TR criteria use a deficit-based approach to the diagnosis. At AuSM, we approach autism from a neurodiversity mindset: this means that we see autism as a different way of processing, communicating, and understanding instead of seeing autistics as people who simply cannot process, communicate, or understand. This doesn’t erase the very real challenges that come with autism, but instead promotes the idea that we can support and accommodate people around those challenges. In our words, here is what the autism diagnosis is.

Remember: these traits can look very different in different people. Each individual will have a different constellation of traits, and no single individual is guaranteed to have any of these traits. Individuals will have their own unique constellation of traits, as well as their own strengths, preferences, and identities. Different people will have different levels of challenges, and these challenges are based on supports and environment. No single behavior can be used to identify autism. If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism. Autism knows no racial, ethnic, or social boundaries. Family income, lifestyle, and educational levels do not affect the chance of a person having autism.

Differences in Socialization and Communication

Autistics don’t socialize or communicate the same way as neurotypicals.

- Expressive language is our ability to communicate our wants, needs, and feelings. Receptive language is our ability to take in information. Someone with autism could have challenges with either or both of these.

- Autistics generally don’t use nonverbal communication in the same way as neurotypicals. Many autistics find eye contact uncomfortable, struggle to interpret nonverbal communication, or use unusual gestures and nonverbals that fall outsides neurotypical norms.

- Processing time is the length of time it takes to process information. Some people need more time than others. It could take five, 10, or even 20 seconds for someone’s brain to comprehend the words they just heard. It’s common for an autistic person to need more processing time when communicating with others.

- “Reciprocity” is the back-and-forth of socialization. It could be literal turn taking in conversation or the give-and-take in a larger relationship. Many autistics don’t find this kind of one-to-one, back-and-forth an easy way to socialize, and they may find success socializing when others appreciate or accept that they infodump, interrupt, or skip small talk.

- Autistics have trouble managing relationships the way neurotypicals would. They might struggle to make or maintain friends, have challenges picking up on red flags, or intensify relationships very quickly.

Many of these “deficits” or challenges are actually differences. When communicating with other neurodivergent people, autistics can have highly-functional social skills.

Restricted, Repetitive Patterns of Behaviors

This criterion refers to stimming, special interests, challenges with change and flexibility, and sensory processing issues.

- Autistics tend to have interests that are incredibly intense and deep. We call these special interests. Sometimes the intensity of these interests can make it hard to do other things. Someone on the spectrum may have a special interest they can talk about at length and repeatedly.

- The neurotypical world can be hard for autistics to predict, so often it is more comfortable to keep routines that are predictable. This means autistics can struggle with changes, need extra support trying something new, or do things exactly the same each time.

- Many people on the spectrum find repeated behaviors (physical, vocal, or otherwise) comforting and useful for emotional regulation. Some people call these behaviors “stims.” A classic example is autistic kids lining up their objects as a form of play.

- Autistics can be hyper (over) or hypo (under) sensitive to sensory inputs. Any given person may be hyper or hypo sensitive to different senses: someone might have a high pain threshold, but be very sensitive to loud sounds.

In addition to the criteria the DSM-5-TR lists out, there are some common features of autism that can make it easier to understand and support our community.

Splinter Skills

Splinter skills are a pattern of development in autism. While a neurotypical tends to develop skills that they can generalize fairly evenly across an area, autistics may have very high skills in one specific area that don’t generalize to another area. We call these differences splinter skills. For example, a person may be able to complete high-level calculus, but they have difficulty keeping a budget.

Executive Functioning

This is the part of the brain in control of strategizing, organizing, working memory, attention, and inhibitory control. People with autism often have difficulties in one or more areas of executive functioning. If an individual on the spectrum procrastinates, has difficulty with memory, struggles to make plans, or has poor time management skills, they may be experiencing executive functioning impairment.

Sensory Processing

All of us receive sensory input from the environment and our bodies that our brains turn into understandable information. Many people on the spectrum have difficulty with the processing step. They can be over- or undersensitive to any sense: Over – It’s too much. Under – I need more.

- Vestibular: sense of balance (movement)

- Proprioceptive: sense of body position (pressure)

- Interoception: sense of the physiological condition of the body (hunger, cramps, exhaustion, and more)

Emotion Regulation

Emotion Regulation is the ability to notice, identify, and respond to your emotions in a way that helps you achieve the outcomes you want. It can include skills to affect your emotions, tolerate the distress, or to decide how to behave in response to the emotions. Autistics may struggle with emotion regulation. Some autistics have alexithymia (difficulty identifying and communicating their own emotions). Some may have very intense emotions, and some may struggle to manage their emotions.

Masking

Masking is when an autistic person hides or suppresses their autistic traits in order to look more neurotypical. Most autistics have some ability to mask, and may choose to mask in particular situations to stay safe or navigate a difficult situation. However, masking for an extended period of time is damaging to mental health and can lead to burnout.

Functioning Levels/Severity and the Spectrum

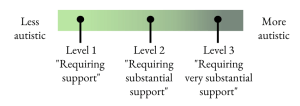

In addition to the traits listed above, the DSM also allows a diagnosing clinician to specify a severity level. It says:

“Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. For either criterion, severity is described in 3 levels: Level 3 – requires very substantial support, Level 2 – Requires substantial support, and Level 1 – requires support.”

Many autistics have pushed back against this as it mimics the idea of functioning levels, which don’t accurately reflect the multi-faceted, fluid nature of functioning. The DSM presents severity/functioning as linear: you’re more or less autistic/functioning. You could picture it like this:

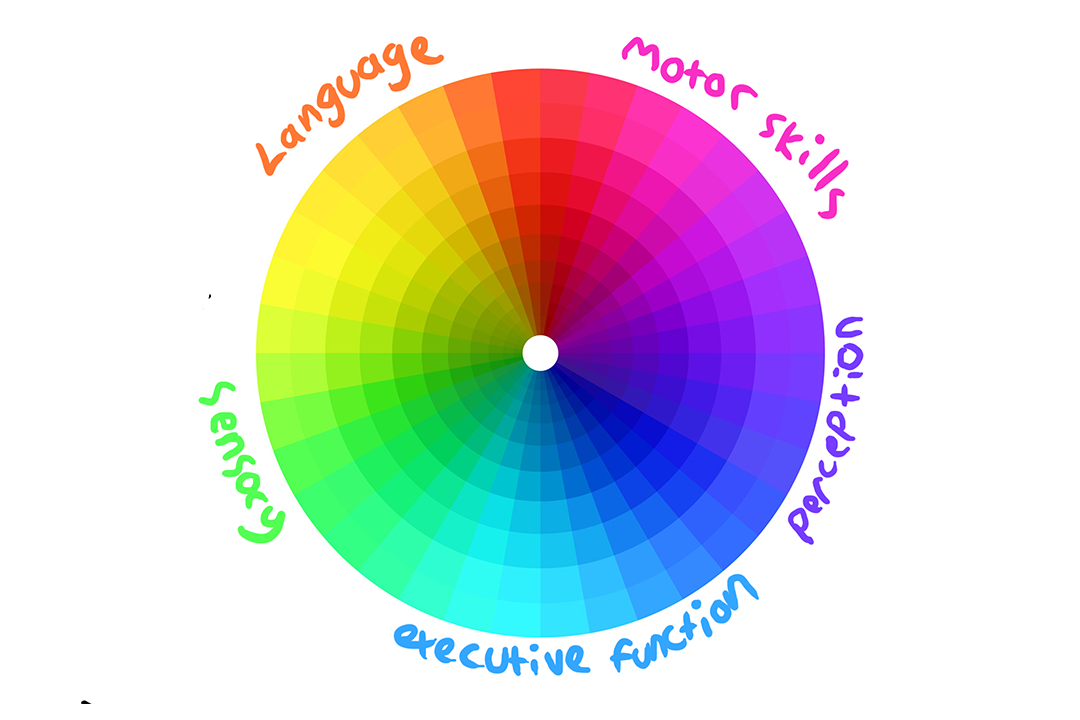

In contrast, newer approaches to autism recognize that functioning labels are not helpful or accurate. This model recognizes that autism encompasses many traits, and a person may have an extreme version of one trait, but almost none of another. It can also help us to understand that each trait varies based on context and supports. This graphic visualization from Rebecca Burgess is a helpful way to understand.

For more information on functioning labels and why the autistic community at large has pushed back against them, check out these resources:

Co-Occurring Conditions

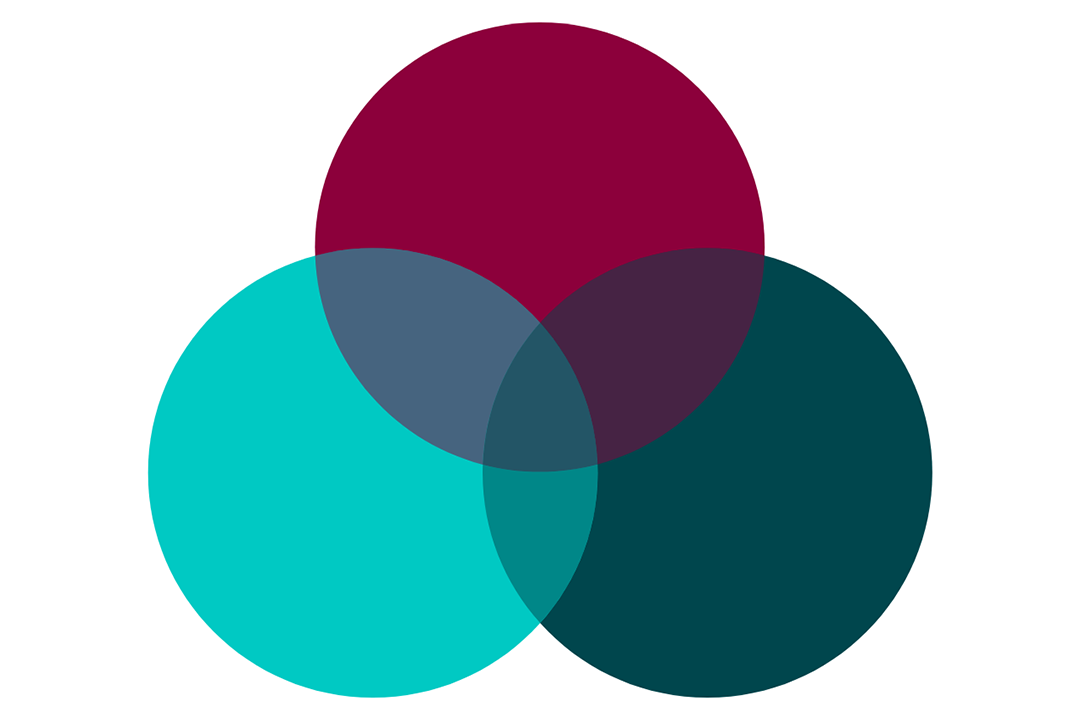

Most autistic individuals have one or more co-occurring conditions, also called comorbidities. There are also a number of other conditions with similar traits to autism: it’s not uncommon for late-diagnosed individuals to receive other diagnoses before they are diagnosed with autism.

Research suggests that between 70 and 95% of children with autism have a co-occurring mental health diagnosis. According to The Spectrum, around 30% of individuals with autism also have an intellectual disability. Around 20% of individuals with autism also have epilepsy.

Some of the most common co-occurring conditions include:

Developmental Disabilities

- Intellectual disability

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- ADHD

Learning Disabilities

- Dyslexia

- Dysgraphia

- Dyscalculia

- Dyspraxia

Mental Health Conditions

- Anxiety

- Depression

- OCD

- Bipolar disorder

- Eating disorders

Physical Health Conditions

- Epilepsy/seizures

- Gastrointestinal/dietary problems

- Sleep challenges

- Motor and coordination difficulties

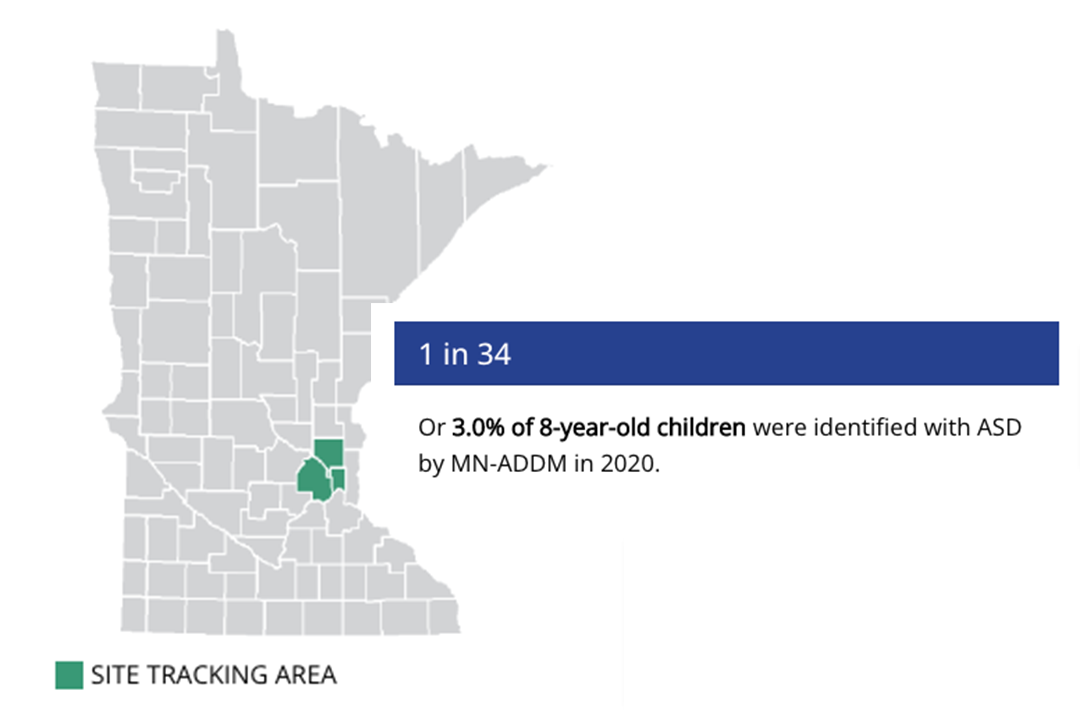

Autism Prevalence

National: 1 in 36

Minnesota: 1 in 34

According to updated research published March 23rd, 2023 by the CDC, 1 in 34 Minnesotans are autistic – an increase from 1 in 36 in the agency’s study from two years ago. That means that 3% of eight-year-old children in Minnesota were identified with autism. Nationally, the CDC found that the prevalence rate is now 1 in 36 throughout the U.S.

In Minnesota, prevalence remains higher among boys, now 4.4 times as likely to be identified with autism compared to girls. Among eight-year-olds, White children (3%) are slightly more likely to be identified with autism than Black children (2.8%), while the rate among Hispanic children is 4% and the rate for Asian/Pacific Islander children is 2.4%. Overall, more Minnesota children are being identified with ASD earlier. More details here.